Posted by Isaac Caswell and Ankur Bapna, Research Scientists, Google Translate Machine translation (MT) technology has made significant advances in recent years, as deep learning has been integrated with natural language processing (NLP). Performance on research benchmarks like WMT have soared, and translation services have improved in quality and expanded to include new languages. Nevertheless, while existing translation services cover languages spoken by the majority of people world wide, they only include around 100 languages in total, just over 1% of those actively spoken globally. Moreover, the languages that are currently represented are overwhelmingly European, largely overlooking regions of high linguistic diversity, like Africa and the Americas.

There are two key bottlenecks towards building functioning translation models for the long tail of languages. The first arises from data scarcity; digitized data for many languages is limited and can be difficult to find on the web due to quality issues with Language Identification (LangID) models. The second challenge arises from modeling limitations. MT models usually train on large amounts of parallel (translated) text, but without such data, models must learn to translate from limited amounts of monolingual text, which is a novel area of research. Both of these challenges need to be addressed for translation models to reach sufficient quality.

In “Building Machine Translation Systems for the Next Thousand Languages”, we describe how to build high-quality monolingual datasets for over a thousand languages that do not have translation datasets available and demonstrate how one can use monolingual data alone to train MT models. As part of this effort, we are expanding Google Translate to include 24 under-resourced languages. For these languages, we created monolingual datasets by developing and using specialized neural language identification models combined with novel filtering approaches. The techniques we introduce supplement massively multilingual models with a self supervised task to enable zero-resource translation. Finally, we highlight how native speakers have helped us realize this accomplishment.

Meet the Data

Automatically gathering usable textual data for under-resourced languages is much more difficult than it may seem. Tasks like LangID, which work well for high-resource languages, are unsuccessful for under-resourced languages, and many publicly available datasets crawled from the web often contain more noise than usable data for the languages they attempt to support. In our early attempts to identify under-resourced languages on the web by training a standard Compact Language Detector v3 (CLD3) LangID model, we too found that the dataset was too noisy to be usable.

As an alternative, we trained a Transformer-based, semi-supervised LangID model on over 1000 languages. This model supplements the LangID task with the MAsked Sequence-to-Sequence (MASS) task to better generalize over noisy web data. MASS simply garbles the input by randomly removing sequences of tokens from it, and trains the model to predict these sequences. We applied the Transformer-based model to a dataset that had been filtered with a CLD3 model and trained to recognize clusters of similar languages.

We then applied the open sourced Term Frequency-Inverse Internet Frequency (TF-IIF) filtering to the resulting dataset to find and discard sentences that were actually in related high-resource languages, and developed a variety of language-specific filters to eliminate specific pathologies. The result of this effort was a dataset with monolingual text in over 1000 languages, of which 400 had over 100,000 sentences. We performed human evaluations on samples of 68 of these languages and found that the majority (>70%) reflected high-quality, in-language content.

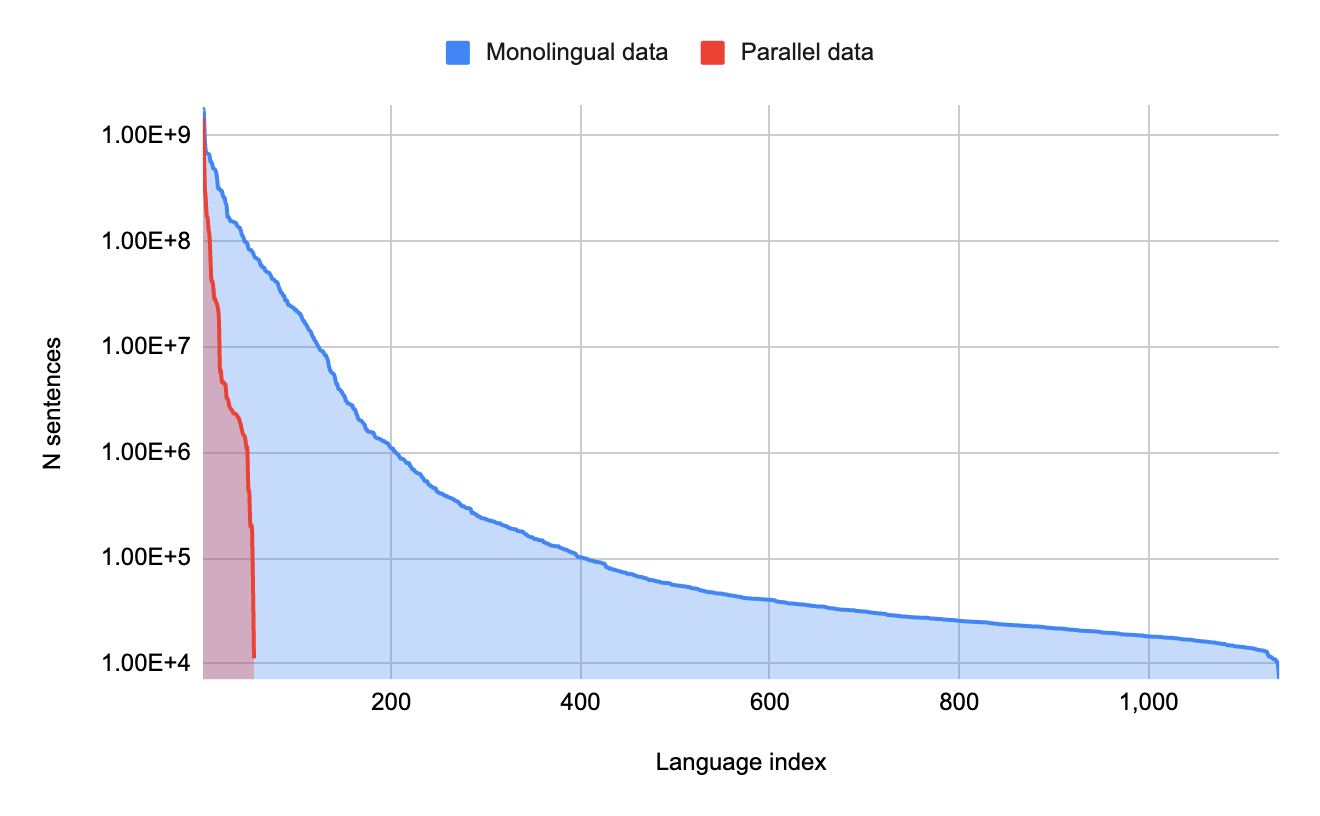

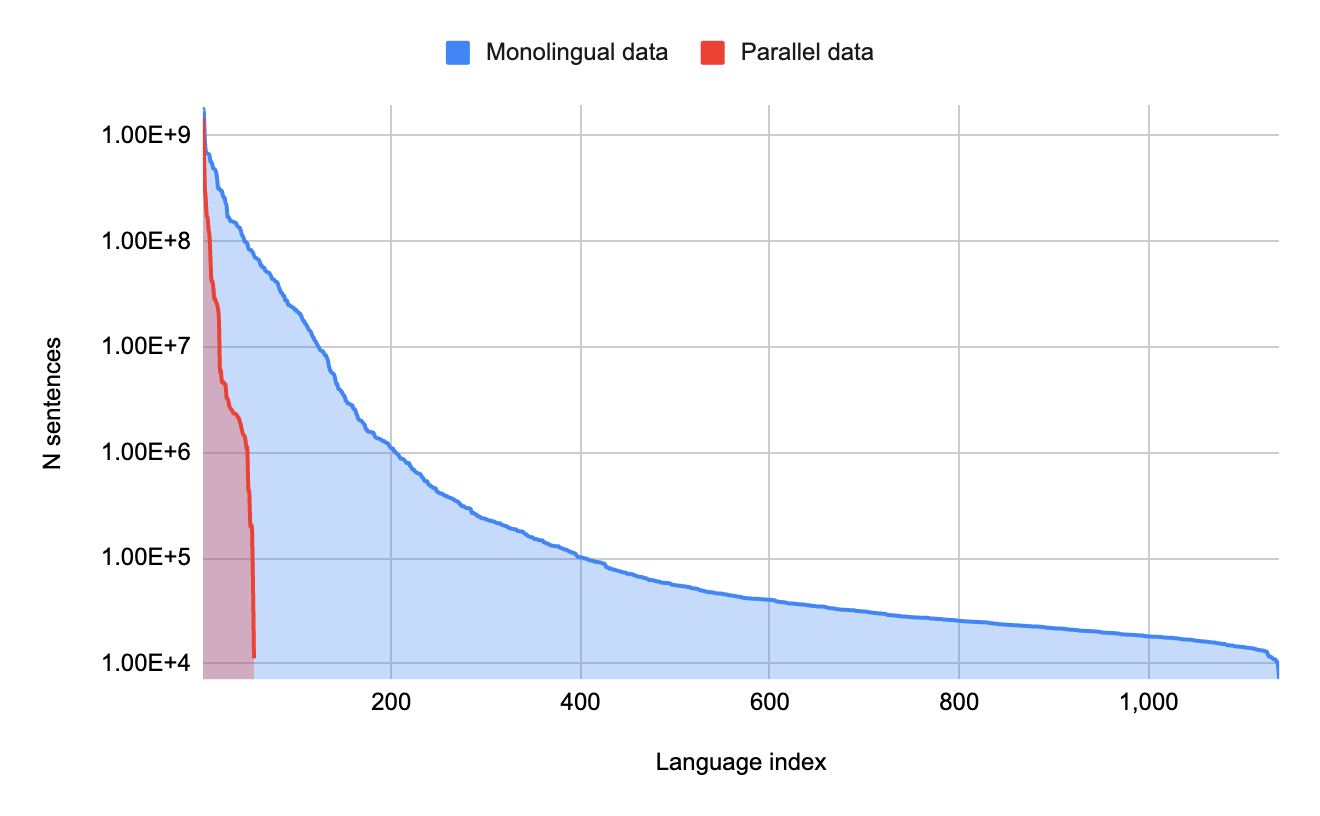

|

| The amount of monolingual data per language versus the amount of parallel (translated) data per language. A small number of languages have large amounts of parallel data, but there is a long tail of languages with only monolingual data. |

Meet the Models

Once we had a dataset of monolingual text in over 1000 languages, we then developed a simple yet practical approach for zero-resource translation, i.e., translation for languages with no in-language parallel text and no language-specific translation examples. Rather than limiting our model to an artificial scenario with only monolingual text, we also include all available parallel text data with millions of examples for higher resource languages to enable the model to learn the translation task. Simultaneously, we train the model to learn representations of under-resourced languages directly from monolingual text using the MASS task. In order to solve this task, the model is forced to develop a sophisticated representation of the language in question, developing a complex understanding of how words relate to other words in a sentence.

Relying on the benefits of transfer learning in massively multilingual models, we train a single giant translation model on all available data for over 1000 languages. The model trains on monolingual text for all 1138 languages and on parallel text for a subset of 112 of the higher-resourced languages.

At training time, any input the model sees has a special token indicating which language the output should be in, exactly like the standard formulation for multilingual translation. Our additional innovation is to use the same special tokens for both the monolingual MASS task and the translation task. Therefore, the token translate_to_french may indicate that the source is in English and needs to be translated to French (the translation task), or it may mean that the source is in garbled French and needs to be translated to fluent French (the MASS task). By using the same tags for both tasks, a translate_to_french tag takes on the meaning, “Produce a fluent output in French that is semantically close to the input,” regardless of whether the input is garbled in the same language or in another language entirely. From the model’s perspective, there is not much difference between the two.

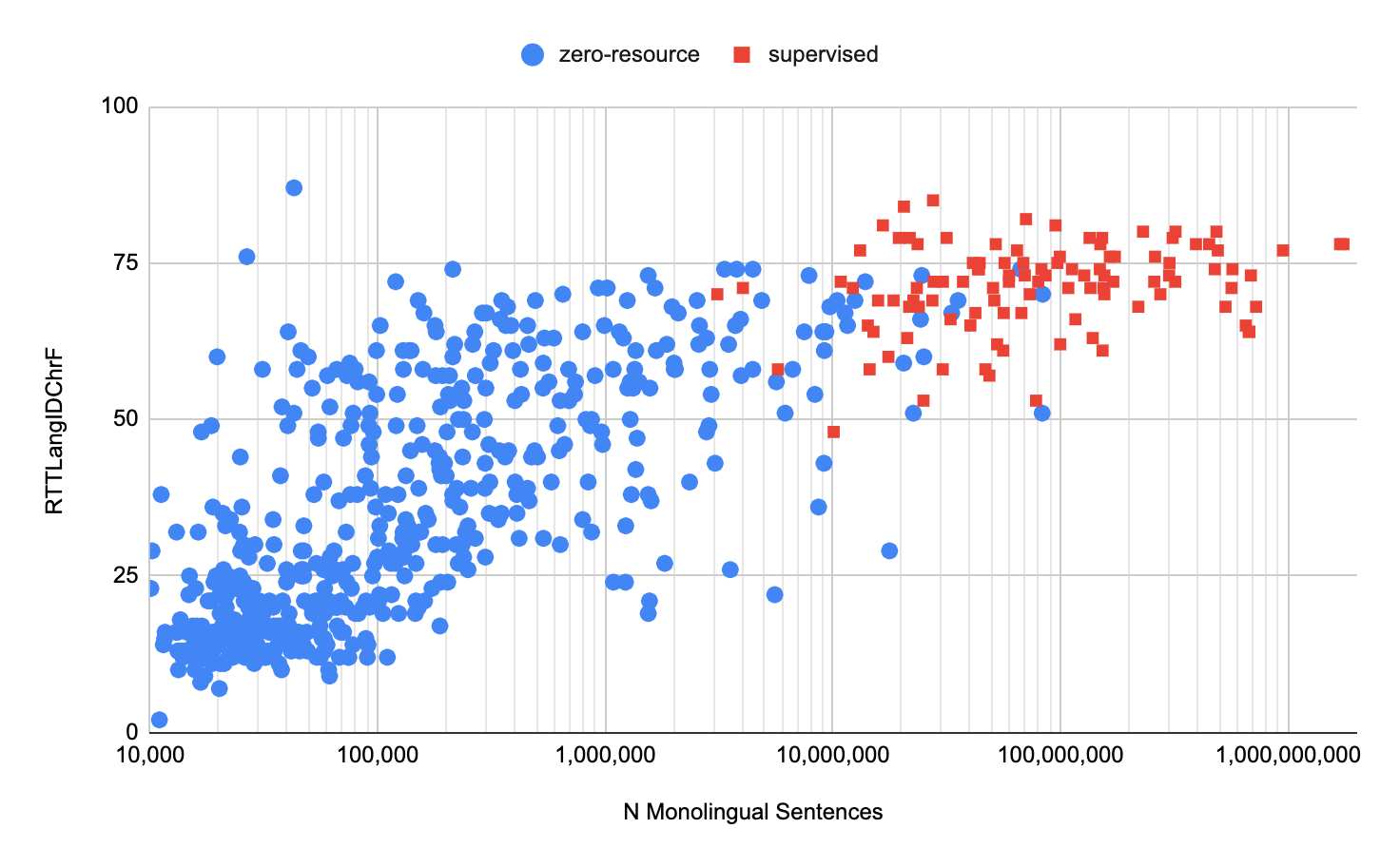

Surprisingly, this simple procedure produces high quality zero-shot translations. The BLEU and ChrF scores for the resulting model are in the 10–40 and 20–60 ranges respectively, indicating mid- to high-quality translation. We observed meaningful translations even for highly inflected languages like Quechua and Kalaallisut, despite these languages being linguistically dissimilar to all other languages in the model. However, we only computed these metrics on the small subset of languages with human-translated evaluation sets. In order to understand the quality of translation for the remaining languages, we developed an evaluation metric based on round-trip translation, which allowed us to see that several hundred languages are reaching high translation quality.

To further improve quality, we use the model to generate large amounts of synthetic parallel data, filter the data based on round-trip translation (comparing a sentence translated into another language and back again), and continue training the model on this filtered synthetic data via back-translation and self-training. Finally, we fine-tune the model on a smaller subset of 30 languages and distill it into a model small enough to be served.

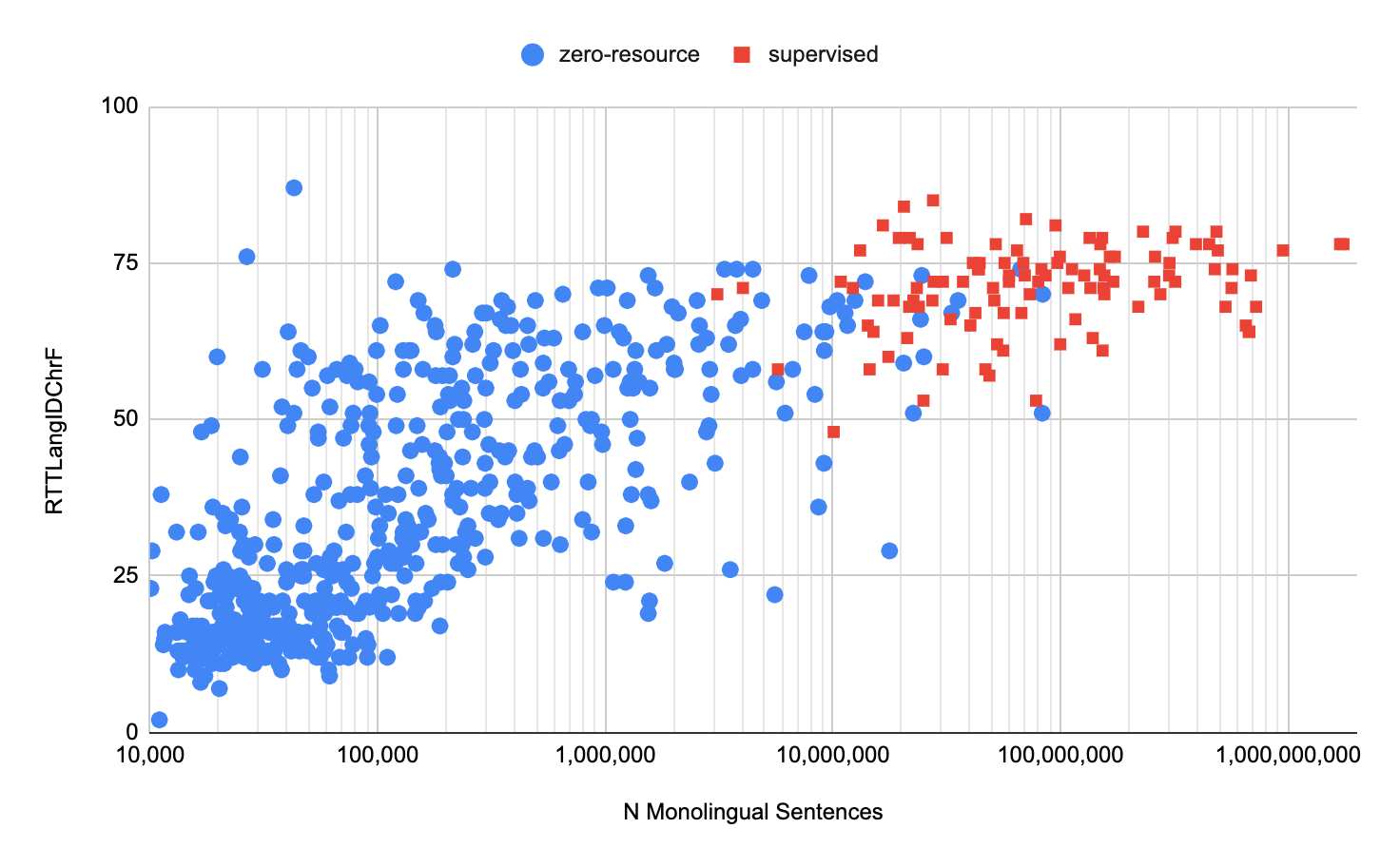

|

| Translation accuracy scores for 638 of the languages supported in our model, using the metric we developed (RTTLangIDChrF), for both the higher-resource supervised languages and the low-resource zero-resource languages. |

Contributions from Native Speakers

Regular communication with native speakers of these languages was critical for our research. We collaborated with over 100 people at Google and other institutions who spoke these languages. Some volunteers helped develop specialized filters to remove out-of-language content overlooked by automatic methods, for instance Hindi mixed with Sanskrit. Others helped with transliterating between different scripts used by the languages, for instance between Meetei Mayek and Bengali, for which sufficient tools didn’t exist; and yet others helped with a gamut of tasks related to evaluation. Native speakers were also key for advising in matters of political sensitivity, like the appropriate name for the language, and the appropriate writing system to use for it. And only native speakers could answer the ultimate question: given the current quality of translation, would it be valuable to the community for Google Translate to support this language?

Closing Notes

This advance is an exciting first step toward supporting more language technologies in under-resourced languages. Most importantly, we want to stress that the quality of translations produced by these models still lags far behind that of the higher-resource languages supported by Google Translate. These models are certainly a useful first tool for understanding content in under-resourced languages, but they will make mistakes and exhibit their own biases. As with any ML-driven tool, one should consider the output carefully.

The complete list of new languages added to Google Translate in this update:

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julia Kreutzer, Orhan Firat, Daan van Esch, Aditya Siddhant, Mengmeng Niu, Pallavi Baljekar, Xavier Garcia, Wolfgang Macherey, Theresa Breiner, Vera Axelrod, Jason Riesa, Yuan Cao, Mia Xu Chen, Klaus Macherey, Maxim Krikun, Pidong Wang, Alexander Gutkin, Apurva Shah, Yanping Huang, Zhifeng Chen, Yonghui Wu, and Macduff Hughes for their contributions to the research, engineering, and leadership of this project.

We would also like to extend our deepest gratitude to the following native speakers and members of affected communities, who helped us in a wide variety of ways: Yasser Salah Eddine Bouchareb (Algerian Arabic); Mfoniso Ukwak (Anaang); Bhaskar Borthakur, Kishor Barman, Rasika Saikia, Suraj Bharech (Assamese); Ruben Hilare Quispe (Aymara); Devina Suyanto (Balinese); Allahserix Auguste Tapo, Bakary Diarrassouba, Maimouna Siby (Bambara); Mohammad Jahangir (Baluchi); Subhajit Naskar (Bengali); Animesh Pathak, Ankur Bapna, Anup Mohan, Chaitanya Joshi, Chandan Dubey, Kapil Kumar, Manish Katiyar, Mayank Srivastava, Neeharika, Saumya Pathak, Tanya Sinha, Vikas Singh (Bhojpuri); Bowen Liang, Ellie Chio, Eric Dong, Frank Tang, Jeff Pitman, John Wong, Kenneth Chang, Manish Goregaokar, Mingfei Lau, Ryan Li, Yiwen Luo (Cantonese); Monang Setyawan (Caribbean Javanese); Craig Cornelius (Cherokee); Anton Prokopyev (Chuvash); Rajat Dogra, Sid Dogra (Dogri); Mohamed Kamagate (Dyula); Chris Assigbe, Dan Ameme, Emeafa Doe, Irene Nyavor, Thierry Gnanih, Yvonne Dumor (Ewe); Abdoulaye Barry, Adama Diallo, Fauzia van der Leeuw, Ibrahima Barry (Fulfulde); Isabel Papadimitriou (Greek); Alex Rudnick (Guarani); Mohammad Khdeir (Gulf Arabic); Paul Remollata (Hiligaynon); Ankur Bapna (Hindi); Mfoniso Ukwak (Ibibio); Nze Lawson (Igbo); D.J. Abuy, Miami Cabansay (Ilocano); Archana Koul, Shashwat Razdan, Sujeet Akula (Kashmiri); Jatin Kulkarni, Salil Rajadhyaksha, Sanjeet Hegde Desai, Sharayu Shenoy, Shashank Shanbhag, Shashi Shenoy (Konkani); Ryan Michael, Terrence Taylor (Krio); Bokan Jaff, Medya Ghazizadeh, Roshna Omer Abdulrahman, Saman Vaisipour, Sarchia Khursheed (Kurdish (Sorani));Suphian Tweel (Libyan Arabic); Doudou Kisabaka (Lingala); Colleen Mallahan, John Quinn (Luganda); Cynthia Mboli (Luyia); Abhishek Kumar, Neeraj Mishra, Priyaranjan Jha, Saket Kumar, Snehal Bhilare (Maithili); Lisa Wang (Mandarin Chinese); Cibu Johny (Malayalam); Viresh Ratnakar (Marathi); Abhi Sanoujam, Gautam Thockchom, Pritam Pebam, Sam Chaomai, Shangkar Mayanglambam, Thangjam Hindustani Devi (Meiteilon (Manipuri)); Hala Ajil (Mesopotamian Arabic); Hamdanil Rasyid (Minangkabau); Elizabeth John, Remi Ralte, S Lallienkawl Gangte,Vaiphei Thatsing, Vanlalzami Vanlalzami (Mizo); George Ouais (MSA); Ahmed Kachkach, Hanaa El Azizi (Morrocan Arabic); Ujjwal Rajbhandari (Newari); Ebuka Ufere, Gabriel Fynecontry, Onome Ofoman, Titi Akinsanmi (Nigerian Pidgin); Marwa Khost Jarkas (North Levantine Arabic); Abduselam Shaltu, Ace Patterson, Adel Kassem, Mo Ali, Yonas Hambissa (Oromo); Helvia Taina, Marisol Necochea (Quechua); AbdelKarim Mardini (Saidi Arabic); Ishank Saxena, Manasa Harish, Manish Godara, Mayank Agrawal, Nitin Kashyap, Ranjani Padmanabhan, Ruchi Lohani, Shilpa Jindal, Shreevatsa Rajagopalan, Vaibhav Agarwal, Vinod Krishnan (Sanskrit); Nabil Shahid (Saraiki); Ayanda Mnyakeni (Sesotho, Sepedi); Landis Baker (Seychellois Creole); Taps Matangira (Shona); Ashraf Elsharif (Sudanese Arabic); Sakhile Dlamini (Swati); Hakim Sidahmed (Tamazight); Melvin Johnson (Tamil); Sneha Kudugunta (Telugu); Alexander Tekle, Bserat Ghebremicael, Nami Russom, Naud Ghebre (Tigrinya); Abigail Annkah, Diana Akron, Maame Ofori, Monica Opoku-Geren, Seth Duodu-baah, Yvonne Dumor (Twi); Ousmane Loum (Wolof); and Daniel Virtheim (Yiddish).

Google Translate adds contextual translation options, more accessible app features and a new design.

Google Translate adds contextual translation options, more accessible app features and a new design.

Google Translate adds contextual translation options, more accessible app features and a new design.

Google Translate adds contextual translation options, more accessible app features and a new design.