Most wearable smart devices and mobile phones have the means to communicate with the user through tactile feedback, enabling applications from simple notifications to sensory substitution for accessibility. Typically, they accomplish this using vibrotactile actuators, which are small electric vibration motors. However, designing a haptic system that is well-targeted and effective for a given task requires experimentation with the number of actuators and their locations in the device, yet most practical applications require standalone on-body devices and integration into small form factors. This combination of factors can be difficult to address outside of a laboratory as integrating these systems can be quite time-consuming and often requires a high level of expertise.

|

| A typical lab setup on the left and the VHP board on the right. |

In “VHP: Vibrotactile Haptics Platform for On-body Applications”, presented at ACM UIST 2021, we develop a low-power miniature electronics board that can drive up to 12 independent channels of haptic signals with arbitrary waveforms. The VHP electronics board can be battery-powered, and integrated into wearable devices and small gadgets. It allows all-day wear, has low latency, battery life between 3 and 25 hours, and can run 12 actuators simultaneously. We show that VHP can be used in bracelet, sleeve, and phone-case form factors. The bracelet was programmed with an audio-to-tactile interface to aid lipreading and remained functional when worn for multiple months by developers. To facilitate greater progress in the field of wearable multi-channel haptics with the necessary tools for their design, implementation, and experimentation, we are releasing the hardware design and software for the VHP system via GitHub.

|

| Front and back sides of the VHP circuit board. |

|

| Block diagram of the system. |

Platform Specifications.

VHP consists of a custom designed circuit board, where the main components are the microcontroller and haptic amplifier, which converts microcontroller’s digital output into signals that drive the actuators. The haptic actuators can be controlled by signals arriving via serial, USB, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), as well as onboard microphones, using an nRF52840 microcontroller, which was chosen because it offers many input and output options and BLE, all in a small package. We added several sensors into the board to provide more experimental flexibility: an on-board digital microphone, an analog microphone amplifier, and an accelerometer. The firmware is a portable C/C++ library that works in the Arduino ecosystem.

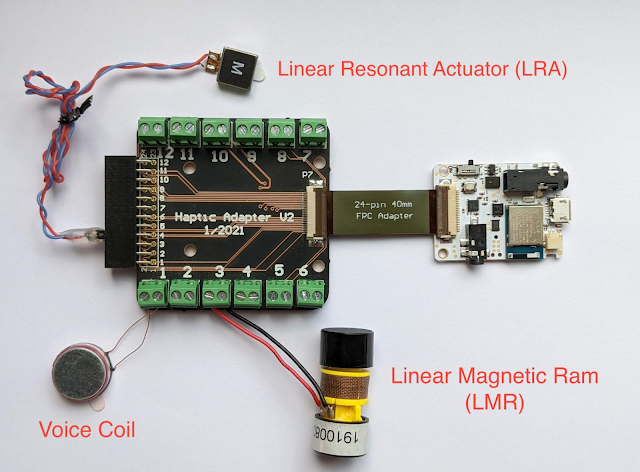

To allow for rapid iteration during development, the interface between the board and actuators is critical. The 12 tactile signals’ wiring have to be quick to set up in order to allow for such development, while being flexible and robust to stand up to prolonged use. For the interface, we use a 24-pin FPC (flexible printed circuit) connector on the VHP. We support interfacing to the actuators in two ways: with a custom flexible circuit board and with a rigid breakout board.

|

| VHP board (small board on the right) connected to three different types of tactile actuators via rigid breakout board (large board on the left). |

Using Haptic Actuators as Sensors

In our previous blog post, we explored how back-EMF in a haptic actuator could be used for sensing and demonstrated a variety of useful applications. Instead of using back-EMF sensing in the VHP system, we measure the electrical current that drives each vibrotactile actuator and use the current load as the sensing mechanism. Unlike back-EMF sensing, this current-sensing approach allows simultaneous sensing and actuation, while minimizing the additional space needed on the board.

One challenge with the current-sensing approach is that there is a wide variety of vibrotactile actuators, each of which may behave differently and need different presets. In addition, because different actuators can be added and removed during prototyping with the adapter board, it would be useful if the VHP were able to identify the actuator automatically. This would improve the speed of prototyping and make the system more novice-friendly.

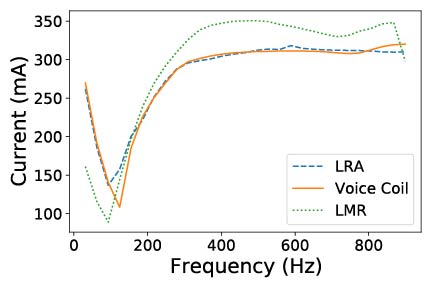

To explore this possibility, we collected current-load data from three off-the-shelf haptic actuators and trained a simple support vector machine classifier to recognize the difference in the signal pattern between actuators. The test accuracy was 100% for classifying the three actuators, indicating that each actuator has a very distinct response.

|

| Different actuators have a different current signature during a frequency sweep, thus allowing for automatic identification. |

Additionally, vibrotactile actuators require proper contact with the skin for consistent control over stimulation. Thus, the device should measure skin contact and either provide an alert or self-adjust if it is not loaded correctly. To test whether a skin contact measuring technique works in practice, we measured the current load on actuators in a bracelet as it was tightened and loosened around the wrist. As the bracelet strap is tightened, the contact pressure between the skin and the actuator increases and the current required to drive the actuator signal increases commensurately.

|

| Current load sensing is responding to touch, while the actuator is driven at 250 Hz frequency. |

|

| Quality of the fit of the bracelet is measured. |

Audio-to-Tactile Feedback

To demonstrate the utility of the VHP platform, we used it to develop an audio-to-tactile feedback device to help with lipreading. Lipreading can be difficult for many speech sounds that look similar (visemes), such as “pin” and “min”. In order to help the user differentiate visemes like these, we attach a microphone to the VHP system, which can then pick up the speech sounds and translate the audio to vibrations on the wrist. For audio-to-tactile translation, we used our previously developed algorithms for real-time audio-to-tactile conversion, available via GitHub. Briefly, audio filters are paired with neural networks to recognize certain viesemes (e.g., picking up the hard consonant “p” in “pin”), and are then translated to vibrations in different parts of the bracelet. Our approach is inspired by tactile phonemic sleeve (TAPS), however the major difference is that in our approach the tactile signal is presented continuously and in real-time.

One of the developers who employs lipreading in daily life wore the bracelet daily for several months and found it to give better information to facilitate lipreading than previous devices, allowing improved understanding of lipreading visemes with the bracelet versus lipreading alone. In the future, we plan to conduct full-scale experiments with multiple users wearing the device for an extended time.

|

| Left: Audio-to-tactile sleeve. Middle: Audio-to-tactile bracelet. Right: One of our developers tests out the bracelets, which are worn on both arms. |

Potential Applications

The VHP platform enables rapid experimentation and prototyping that can be used to develop techniques for a variety of applications. For example:

- Rich haptics on small devices: Expanding the number of actuators on mobile phones, which typically only have one or two, could be useful to provide additional tactile information. This is especially useful as fingers are sensitive to vibrations. We demonstrated a prototype mobile phone case with eight vibrotactile actuators. This could be used to provide rich notifications and enhance effects in a mobile game or when watching a video.

- Lab psychophysical experiments: Because VHP can be easily set up to send and receive haptic signals in real time, e.g., from a Jupyter notebook, it could be used to perform real-time haptic experiments.

- Notifications and alerts: The wearable VHP could be used to provide haptic notifications from other devices, e.g., alerting if someone is at the door, and could even communicate distinguishable alerts through use of multiple actuators.

- Sensory substitution: Besides the lipreading assistance example above, there are many other potential applications for accessibility using sensory substitution, such as visual-to-tactile sensing or even sensing magnetic fields.

- Loading sensing: The ability to sense from the haptic actuator current load is unique to our platform, and enables a variety of features, such as pressure sensing or automatically adjusting actuator output.

|

| Integrating eight voice coils into a phone case. We used loading sensing to understand which voice coils are being touched. |

What's next?

We hope that others can utilize the platform to build a diverse set of applications. If you are interested and have ideas about using our platform or want to receive updates, please fill out this form. We hope that with this platform, we can help democratize the use of haptics and inspire a more widespread use of tactile devices.

Acknowledgments

This work was done by Artem Dementyev, Pascal Getreuer, Dimitri Kanevsky, Malcolm Slaney and Richard Lyon. We thank Alex Olwal, Thad Starner, Hong Tan, Charlotte Reed, Sarah Sterman for valuable feedback and discussion on the paper. Yuhui Zhao, Dmitrii Votintcev, Chet Gnegy, Whitney Bai and Sagar Savla for feedback on the design and engineering.