Last year we launched Recorder, a new kind of recording app that made audio recording smarter and more useful by leveraging on-device machine learning (ML) to transcribe the recording, highlight audio events, and suggest appropriate tags for titles. Recorder makes editing, sharing and searching through transcripts easier. Yet because Recorder can transcribe very long recordings (up to 18 hours!), it can still be difficult for users to find specific sections, necessitating a new solution to quickly navigate such long transcripts.

To increase the navigability of content, we introduce Smart Scrolling, a new ML-based feature in Recorder that automatically marks important sections in the transcript, chooses the most representative keywords from each section, and then surfaces those keywords on the vertical scrollbar, like chapter headings. The user can then scroll through the keywords or tap on them to quickly navigate to the sections of interest. The models used are lightweight enough to be executed on-device without the need to upload the transcript, thus preserving user privacy.

|

| Smart Scrolling feature UX |

Under the hood

The Smart Scrolling feature is composed of two distinct tasks. The first extracts representative keywords from each section and the second picks which sections in the text are the most informative and unique.

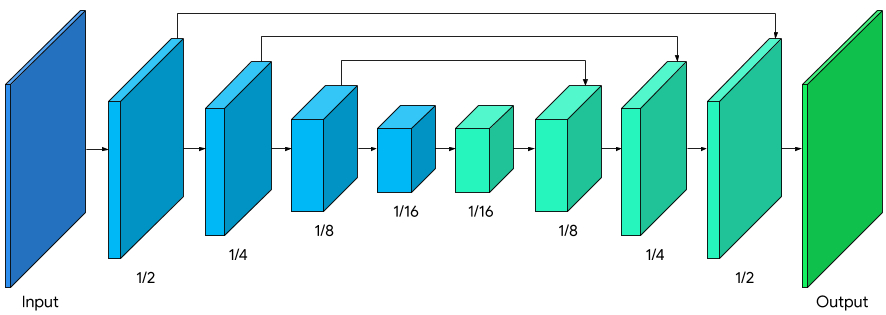

For each task, we utilize two different natural language processing (NLP) approaches: a distilled bidirectional transformer (BERT) model pre-trained on data sourced from a Wikipedia dataset, alongside a modified extractive term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) model. By using the bidirectional transformer and the TF-IDF-based models in parallel for both the keyword extraction and important section identification tasks, alongside aggregation heuristics, we were able to harness the advantages of each approach and mitigate their respective drawbacks (more on this in the next section).

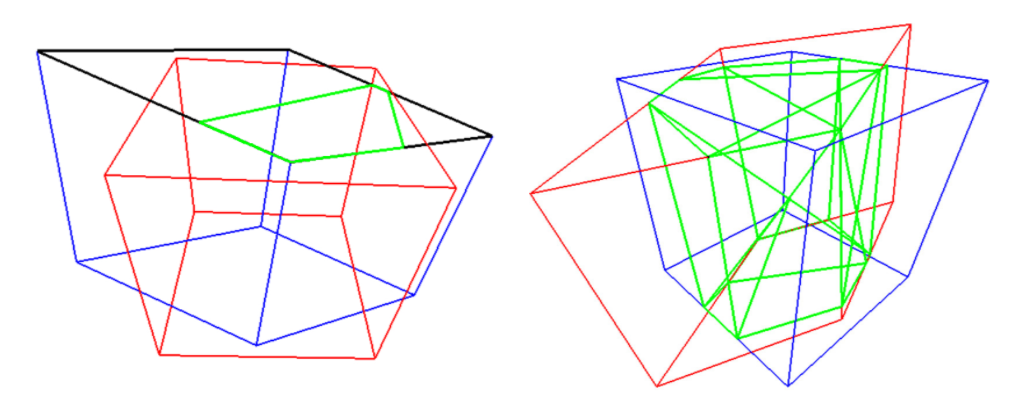

The bidirectional transformer is a neural network architecture that employs a self-attention mechanism to achieve context-aware processing of the input text in a non-sequential fashion. This enables parallel processing of the input text to identify contextual clues both before and after a given position in the transcript.

|

| Bidirectional Transformer-based model architecture |

The extractive TF-IDF approach rates terms based on their frequency in the text compared to their inverse frequency in the trained dataset, and enables the finding of unique representative terms in the text.

Both models were trained on publicly available conversational datasets that were labeled and evaluated by independent raters. The conversational datasets were from the same domains as the expected product use cases, focusing on meetings, lectures, and interviews, thus ensuring the same word frequency distribution (Zipf’s law).

Extracting Representative Keywords

The TF-IDF-based model detects informative keywords by giving each word a score, which corresponds to how representative this keyword is within the text. The model does so, much like a standard TF-IDF model, by utilizing the ratio of the number of occurrences of a given word in the text compared to the whole of the conversational data set, but it also takes into account the specificity of the term, i.e., how broad or specific it is. Furthermore, the model then aggregates these features into a score using a pre-trained function curve. In parallel, the bidirectional transformer model, which was fine tuned on the task of extracting keywords, provides a deep semantic understanding of the text, enabling it to extract precise context-aware keywords.

The TF-IDF approach is conservative in the sense that it is prone to finding uncommon keywords in the text (high bias), while the drawback for the bidirectional transformer model is the high variance of the possible keywords that can be extracted. But when used together, these two models complement each other, forming a balanced bias-variance tradeoff.

Once the keyword scores are retrieved from both models, we normalize and combine them by utilizing NLP heuristics (e.g., the weighted average), removing duplicates across sections, and eliminating stop words and verbs. The output of this process is an ordered list of suggested keywords for each of the sections.

Rating A Section’s Importance

The next task is to determine which sections should be highlighted as informative and unique. To solve this task, we again combine the two models mentioned above, which yield two distinct importance scores for each of the sections. We compute the first score by taking the TF-IDF scores of all the keywords in the section and weighting them by their respective number of appearances in the section, followed by a summation of these individual keyword scores. We compute the second score by running the section text through the bidirectional transformer model, which was also trained on the sections rating task. The scores from both models are normalized and then combined to yield the section score.

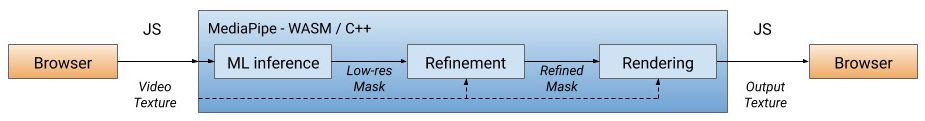

|

| Smart Scrolling pipeline architecture |

Some Challenges

A significant challenge in the development of Smart Scrolling was how to identify whether a section or keyword is important - what is of great importance to one person can be of less importance to another. The key was to highlight sections only when it is possible to extract helpful keywords from them.

To do this, we configured the solution to select the top scored sections that also have highly rated keywords, with the number of sections highlighted proportional to the length of the recording. In the context of the Smart Scrolling features, a keyword was more highly rated if it better represented the unique information of the section.

To train the model to understand this criteria, we needed to prepare a labeled training dataset tailored to this task. In collaboration with a team of skilled raters, we applied this labeling objective to a small batch of examples to establish an initial dataset in order to evaluate the quality of the labels and instruct the raters in cases where there were deviations from what was intended. Once the labeling process was complete we reviewed the labeled data manually and made corrections to the labels as necessary to align them with our definition of importance.

Using this limited labeled dataset, we ran automated model evaluations to establish initial metrics on model quality, which were used as a less-accurate proxy to the model quality, enabling us to quickly assess the model performance and apply changes in the architecture and heuristics. Once the solution metrics were satisfactory, we utilized a more accurate manual evaluation process over a closed set of carefully chosen examples that represented expected Recorder use cases. Using these examples, we tweaked the model heuristics parameters to reach the desired level of performance using a reliable model quality evaluation.

Runtime Improvements

After the initial release of Recorder, we conducted a series of user studies to learn how to improve the usability and performance of the Smart Scrolling feature. We found that many users expect the navigational keywords and highlighted sections to be available as soon as the recording is finished. Because the computation pipeline described above can take a considerable amount of time to compute on long recordings, we devised a partial processing solution that amortizes this computation over the whole duration of the recording. During recording, each section is processed as soon as it is captured, and then the intermediate results are stored in memory. When the recording is done, Recorder aggregates the intermediate results.

When running on a Pixel 5, this approach reduced the average processing time of an hour long recording (~9K words) from 1 minute 40 seconds to only 9 seconds, while outputting the same results.

Summary

The goal of Recorder is to improve users’ ability to access their recorded content and navigate it with ease. We have already made substantial progress in this direction with the existing ML features that automatically suggest title words for recordings and enable users to search recordings for sounds and text. Smart Scrolling provides additional text navigation abilities that will further improve the utility of Recorder, enabling users to rapidly surface sections of interest, even for long recordings.

Acknowledgments

Bin Zhang, Sherry Lin, Isaac Blankensmith, Henry Liu, Vincent Peng, Guilherme Santos, Tiago Camolesi, Yitong Lin, James Lemieux, Thomas Hall, Kelly Tsai, Benny Schlesinger, Dror Ayalon, Amit Pitaru, Kelsie Van Deman, Console Chen, Allen Su, Cecile Basnage, Chorong Johnston, Shenaz Zack, Mike Tsao, Brian Chen, Abhinav Rastogi, Tracy Wu, Yvonne Yang.