Posted by the Google Fonts team The Google Fonts catalog now includes Korean web fonts for designers and developers working with the nation's unique Hangul writing system. While some of the fonts themselves have been available in beta for years now, we introduced official support for Korean earlier this month after devising a more efficient means of serving Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK) font files, which have very large character sets and file sizes.

We've always wanted to offer CJK fonts, and over the years we've worked on foundational technologies such as WOFF2 and CSS3 unicode-range in order to make this possible. Last year, Google engineers experimented with different approaches to slicing fonts into smaller subsets, and found that certain techniques had very good results that enabled this launch.

The Hangul script is distinct from Chinese Hanzi and Japanese Kanji characters. In some ways, it shares greater similarity with Western writing systems because it is constructed from a phonetic alphabet. Whereas the visual features of Hanzi and Kanji logograms give no direct indication of their pronunciation, Hangul is a phonographic script in which written words are built from their constituent sounds.

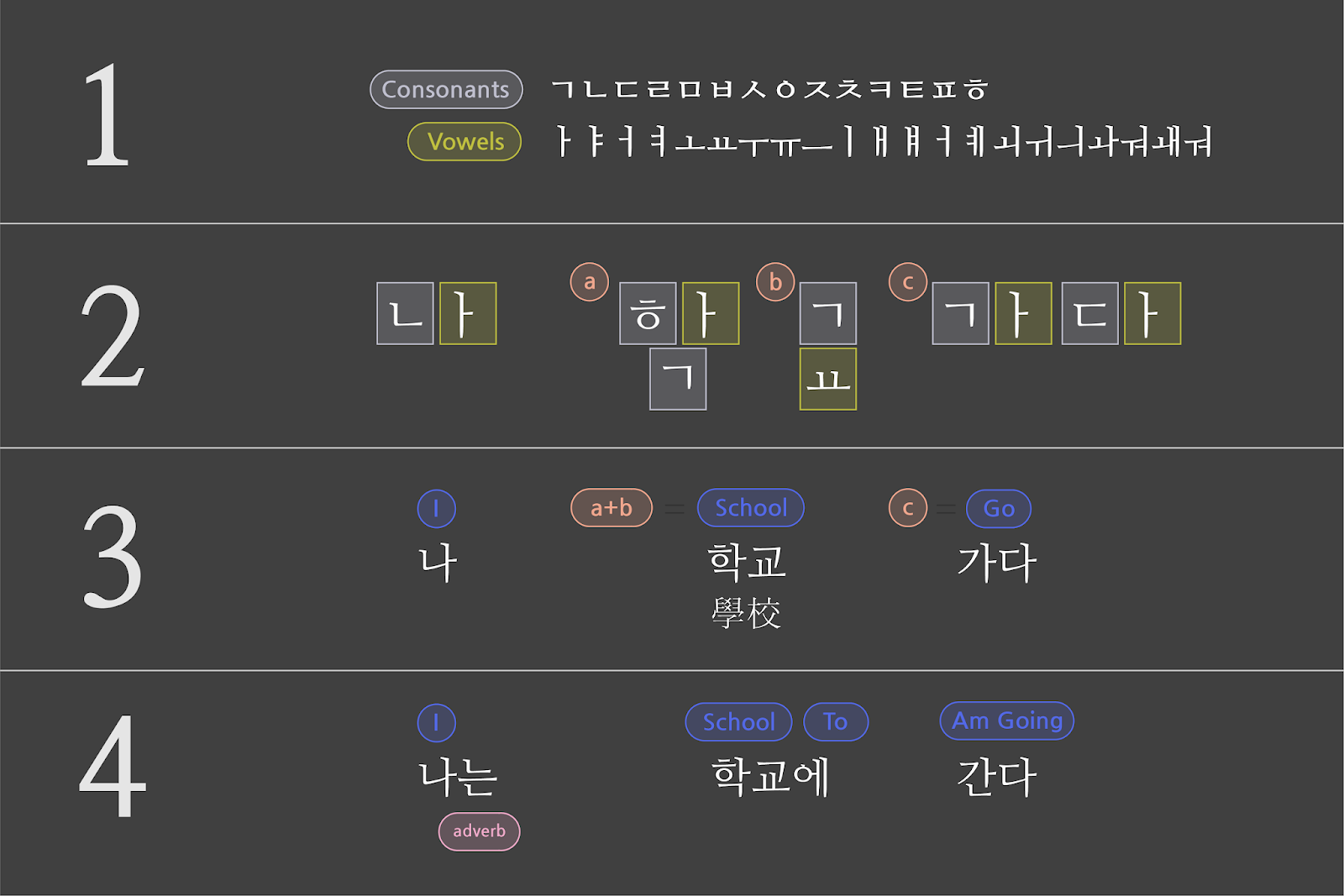

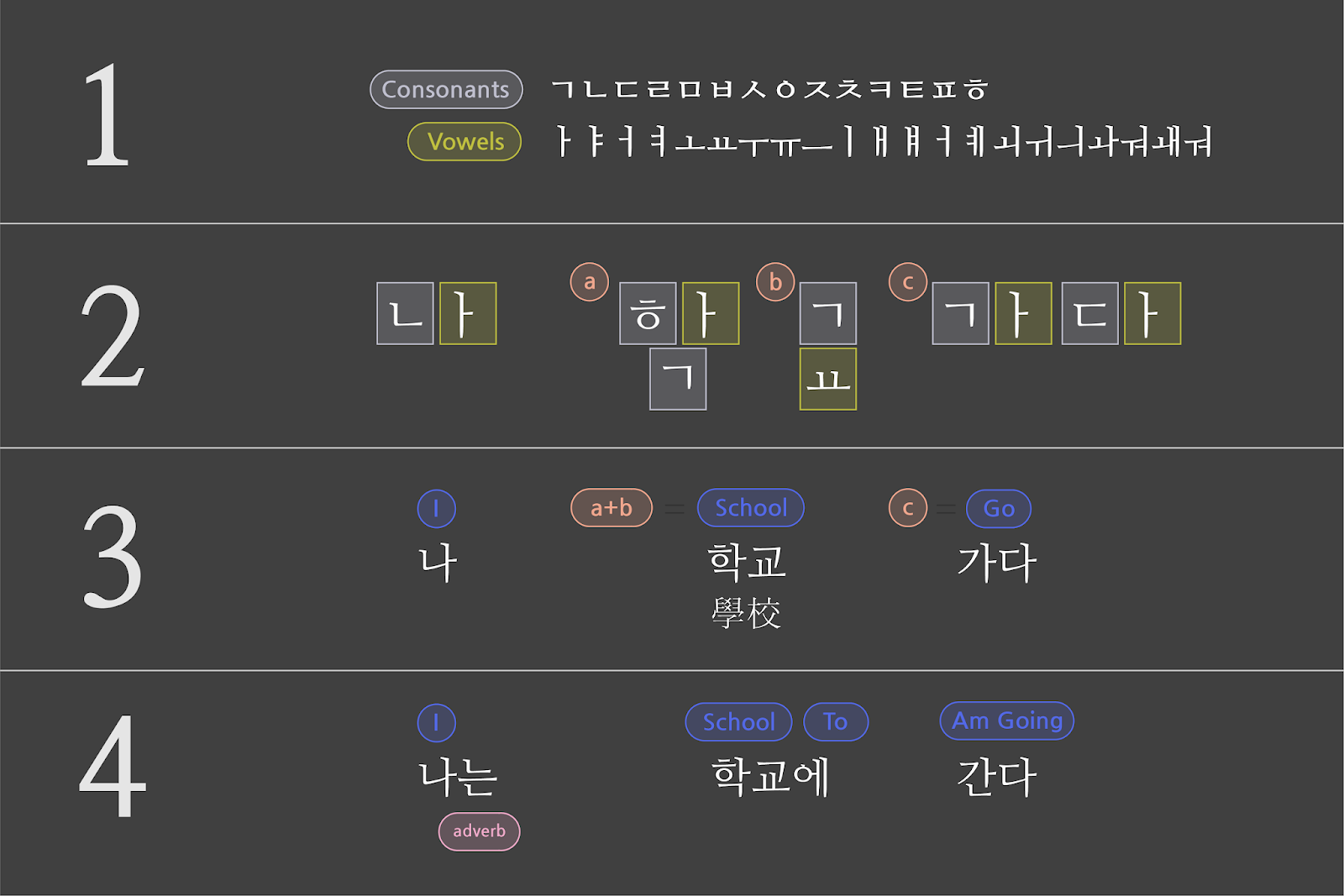

Hangul starts with a set of 19 consonants and 21 vowels (1). When writing a sentence, individual characters are first identified (2), then combined into blocks that represent compete words (3), and finally conjugated and arranged in grammatical form to create a sentence (4).

Despite the elegant logic underlying Hangul script, Korean fonts present the same basic difficulty for developers that Chinese and Japanese fonts do. Hangul characters may be constructed from just 40 basic elements, but the final forms add up quickly. Korean fonts eventually require over ten thousand characters, meaning the files are too large for most users to download so that they will appear instantly upon visiting a website. A typical full Korean font hovers around 4Mb, whereas even fairly extensive Latin fonts rarely exceed 250Kb.

During the time that Korean fonts were only available on the Google Fonts Early Access system, we were surprised that many web developers were willing to accept the latency implications of serving full font files to their users. Still, in order to graduate these fonts out of our Early Access system, we needed to devise a way for them to work for a wider cross-section of web users, especially those with relatively slow connections.

The Google Fonts API offers larger font files as several subsets, such as "latin" and "cyrillic." When the service launched, these subsets had to be selected by developers. For a few years, we've enabled the 'unicode-range' property of CSS3 for browsers that support it. This means when a large font file is sliced into subsets, the ranges of the Unicode characters in each subset are declared as part of the @font-face declaration. This allows browsers to fetch only a particular subset when those characters appear in a web page.

One of the key benefits of the Google Fonts API is cross-site caching, and this benefit continues to apply to the delivery of font subsets through unicode-range. The font files we serve are used by many domains, so after you visit a site and your browser downloads its fonts, the files are saved in the browser's cache. Then the next time you visit another site that uses the same font files, there's no need for your browser to download it again. This latency benefit only increases over time, and since the many subsets of large font files are cached the same way, you'll see the same cross-site benefits with our CJK fonts.

Over the years we have worked with the W3C and browser developers to ensure that unicode-range would become well supported. Now that Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge have shipped this feature, there is enough support to enable a new means of delivering Korean web fonts that works seamlessly for these browsers.

Support for the unicode-range feature has become widespread, according to caniuse.com

In order maximize efficiency, we wanted to know which characters it made the most sense to cluster together in a subset. We devised a slicing strategy by analyzing text on the Korean-language web to extract patterns of Unicode characters, building topic models of which ones tend to appear together on the same page.

As we evaluated different slicing strategies to decide which Korean characters to include in each subset, our goal was to minimize both the number of subsets and the number of requests. If we sliced the script into 1,000 arbitrary subsets, without factoring in usage and commonality, we would get way too many HTTP requests. We built a testing framework to see how a variety of strategies worked with real-world traffic using our Early Access system, and we launched Korean fonts in our directory with the most efficient one we've found so far.

Strategy 1 is no slicing. The best strategy had 20 times fewer connection requests than the worst, which simply divides the font into equal parts without accounting for patterns of language use.

Moving forward, we think we can do even better. With our scale, a small improvement can justify a lot of effort. By continuing to use our testing framework on different approaches to slicing, we can tune our serving to be as efficient as possible. For the web developers who use our API, and all end users, these kinds of changes are totally transparent and don't require any further work on your part. For example, when WOFF2 came out in 2015, every user with a browser supporting WOFF2 got a 25% faster experience. We transparently make things better for all users on an ongoing basis, and there's enormous potential for future improvements in the delivery of CJK fonts.

This launch began with five Korean fonts originally designed by the leading Korean type foundry Sandoll for Naver. Since the initial launch, we have grown the collection to 23 Korean families, and to showcase them we commissioned a digital specimen website from Math Practice, a digital design studio in New York City. Here you can see beautiful Korean typography in action—and with fast page loads made possible by our new slicing technique.

Thanks to SooYoung Jang, Irin Kim, E Roon Kang, Wonyoung So, Guhong Min, Hannah Son, Aaron Bell, Marc Foley, and all the typeface designers involved in growing the Korean fonts collection and developing the minisite.