Quantum computing integrates the two largest technological revolutions of the last half century, information technology and quantum mechanics. If we compute using the rules of quantum mechanics, instead of binary logic, some intractable computational tasks become feasible. An important goal in the pursuit of a universal quantum computer is the determination of the smallest computational task that is prohibitively hard for today’s classical computers. This crossover point is known as the “quantum supremacy” frontier, and is a critical step on the path to more powerful and useful computations.

In “Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices” published in Nature Physics (arXiv here), we present the theoretical foundation for a practical demonstration of quantum supremacy in near-term devices. It proposes the task of sampling bit-strings from the output of random quantum circuits, which can be thought of as the “hello world” program for quantum computers. The upshot of the argument is that the output of random chaotic systems (think butterfly effect) become very quickly harder to predict the longer they run. If one makes a random, chaotic qubit system and examines how long a classical system would take to emulate it, one gets a good measure of when a quantum computer could outperform a classical one. Arguably, this is the strongest theoretical proposal to prove an exponential separation between the computational power of classical and quantum computers.

Determining where exactly the quantum supremacy frontier lies for sampling random quantum circuits has rapidly become an exciting area of research. On one hand, improvements in classical algorithms to simulate quantum circuits aim to increase the size of the quantum circuits required to establish quantum supremacy. This forces an experimental quantum device with a sufficiently large number of qubits and low enough error rates to implement circuits of sufficient depth (i.e the number of layers of gates in the circuit) to achieve supremacy. On the other hand, we now understand better how the particular choice of the quantum gates used to build random quantum circuits affects the simulation cost, leading to improved benchmarks for near-term quantum supremacy (available for download here), which are in some cases quadratically more expensive to simulate classically than the original proposal.

Sampling from random quantum circuits is an excellent calibration benchmark for quantum computers, which we call cross-entropy benchmarking. A successful quantum supremacy experiment with random circuits would demonstrate the basic building blocks for a large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer. Furthermore, quantum physics has not yet been tested for highly complex quantum states such as this.

|

| Space-time volume of a quantum circuit computation. The computational cost for quantum simulation increases with the volume of the quantum circuit, and in general grows exponentially with the number of qubits and the circuit depth. For asymmetric grids of qubits, the computational space-time volume grows slower with depth than for symmetric grids, and can result in circuits exponentially easier to simulate. |

Beyond achieving quantum supremacy, a quantum platform should offer clear applications. In our paper, we apply our algorithms towards computational problems in quantum statistical-mechanics using complex multi-qubit gates (as opposed to the two-qubit gates designed for a digital quantum processor with surface code error correction). We show that our devices can be used to study fundamental properties of materials, e.g. microscopic differences between metals and insulators. By extending these results to next-generation devices with ~50 qubits, we hope to answer scientific questions that are beyond the capabilities of any other computing platform.

|

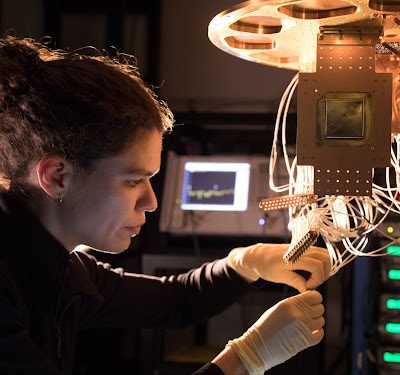

| Photograph of two gmon superconducting qubits and their tunable coupler developed by Charles Neill and Pedram Roushan. |