Today, in collaboration with Adobe, we are responding to the call for Serif! We are pleased to announce Noto Serif CJK, the long-awaited companion to Noto Sans CJK released in 2014. Like Noto Sans CJK, Noto Serif CJK supports Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, all in one font.

A serif-style CJK font goes by many names: Song (宋体) in Mainland China, Ming (明體) in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, Minchō (明朝) in Japan, and Myeongjo (명조) or Batang (바탕) in Korea. The names and writing styles originated during the Song and Ming dynasties in China, when China's wood-block printing technique became popular. Characters were carved along the grain of the wood block. Horizontal strokes were easy to carve and vertical strokes were difficult; this resulted in thinner horizontal strokes and wider vertical ones. In addition, subtle triangular ornaments were added to the end of horizontal strokes to simulate Chinese Kai (楷体) calligraphy. This style continues today and has become a popular typeface style.

Serif fonts, which are considered more traditional with calligraphic aesthetics, are often used for long paragraphs of text such as body text of web pages or ebooks. Sans-serif fonts are often used for user interfaces of websites/apps and headings because of their simplicity and modern feeling.

The Noto Serif CJK package offers the same features as Noto Sans CJK:

- It has comprehensive character coverage for the four languages. This includes the full coverage of CJK Ideographs with variation support for four regions, Kangxi radicals, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul and other CJK symbols and letters in the Unicode Basic Multilingual Plane of Unicode. It also provides a limited coverage of CJK Ideographs in Plane 2 of Unicode, as necessary to support standards from China and Japan.

Simplified Chinese | Supports GB 18030 and China’s latest standard Table of General Chinese Characters (通用规范汉字表) published in 2013. |

Traditional Chinese | Supports BIG5, and Traditional Chinese glyphs are compliant to glyph standard of Taiwan Ministry of Education (教育部國字標準字體). |

Japanese | Supports all of the kanji in JIS X 0208, JIS X 0213, and JIS X 0212 to include all kanji in Adobe-Japan1-6. |

Korean | The best font for typesetting classic Korean documents in Hangul and Hanja such as Humninjeongeum manuscript, a UNESCO World Heritage. Supports over 1.5 million archaic Hangul syllables and 11,172 modern syllables as well as all CJK ideographs in KS X 1001 and KS X 1002 |

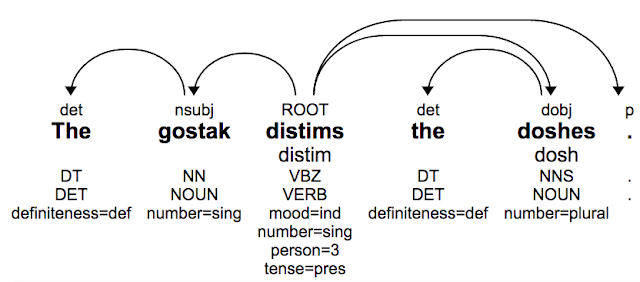

- It respects diversity of regional writing conventions for the same character. The example below shows the four glyphs of '述' (describe) in four languages that have subtle differences.

Noto Serif CJK’s support of character and glyph set standards for the four languages

|

| From left to right are glyphs of '述' in S. Chinese, T. Chinese, Japanese and Korean. This character means "describe". |

- It is offered in seven weights: ExtraLight, Light, Regular, Medium, SemiBold, Bold, and Black. Noto Serif CJK supports 43,027 encoded characters and includes 65,535 glyphs (the maximum number of glyphs that can be included in a single font). The seven weights, when put together, have almost a half-million glyphs. The weights are compatible with Google's Material Design standard fonts, Roboto, Noto Sans and Noto Serif(Latin-Greek-Cyrillic fonts in the Noto family).

- Seven weights of Noto Serif CJK

- It supports vertical text layout and is compliant with the Unicode vertical text layout standard. The shape, orientation, and position of particular characters (e.g., brackets and kana letters) are changed when the writing direction of the text is vertical.

The sheer size of this project also required regional expertise! Glyph design would not have been possible without leading East Asian type foundries Changzhou SinoType Technology, Iwata Corporation, and Sandoll Communications.

Noto Serif CJK is open source under the SIL Open Font License, Version 1.1. We invite individual users to install and use these fonts in their favorite authoring apps; developers to bundle these fonts with your apps, and OEMs to embed them into their devices. The fonts are free for everyone to use!

Noto Serif CJK font download:https://www.google.com/get/noto

Noto Serif CJK on GitHub:https://github.com/googlei18n/noto-cjk

Adobe's landing page for this release: http://adobe.ly/SourceHanSerif

Source Han Serif on GitHub: https://github.com/adobe-fonts/source-han-serif/tree/release/

By Xiangye Xiao and Jungshik Shin, Internationalization Engineering team