At Google, open source is at the core of our infrastructure, processes, and culture. For the last 19 years, Google’s Open Source Programs Office (OSPO) has enabled our organization to support open source ecosystems through funding, training, mentorship and direct contribution. Every year for the last 5 years, roughly 10% of our workforce has contributed to open source projects as part of their work as well as in their personal time. We’re focused on investing in and protecting open source communities and infrastructure, as well as expanding access to open source opportunities around the world. Every day we seek to promote open and connected ecosystems as the foundation of technological advancement.

For the last four years, researchers in Google's Open Source Programs Office (OSPO) have analyzed our open source contribution activity annually to identify trends and changes in behavior. The goal of this effort has been to increase transparency and accountability across all of the communities we engage with, as well as provide feedback indicators for Alphabet’s internal tools, processes, and policies. In this iteration, our 2022 open source contribution metrics were remarkably consistent with what we found in 2021, which gives us confidence that what we're measuring is a good representation of open source behavior, especially after the extreme outlier year of 2020.

Security remains a priority

At Alphabet, open source software remains a critical component of our infrastructure, products, and services and we continue to rely on the health and availability of open source projects. Through internal efforts and collaboration with industry-led efforts such as OpenSSF, Alphabet is committed to bolstering the security posture of projects, users, and developers of open source software.

In 2021, Google began funding two Linux Foundation contractors to focus exclusively on security, and in 2022 we've continued to sponsor their work to eliminate fragile C language features and APIs in the kernel. We also continue to support the Rust-in-Linux project, with the goal of improving memory safety, strengthening APIs, and reducing the number of bugs overall in the project. In late 2022, Rust infrastructure support landed in the upstream kernel.

The deps.dev project released a public BigQuery dataset, allowing anyone to explore and analyze the dependencies, advisories, ownership, license, and other metadata of open source packages across supported ecosystems, and explore how this metadata has changed over time.

In 2022 we announced:

- The OSV-Scanner, a free tool enabling open source developers and users to identify and remediate known vulnerabilities in their project's OSS dependencies. The OSV-Scanner provides a supported frontend to the OSV database which connects a project’s list of dependencies with the vulnerabilities that affect them.

- The GOSST Upstream Team, a dedicated staff of Google open source security engineers who spend 100% of their time working closely with upstream maintainers to improve the security of critical open source projects.

- Graph for Understanding Artifact Composition (GUAC) which aggregates software security metadata into a high fidelity graph database–normalizing entity identities and mapping standard relationships between them.

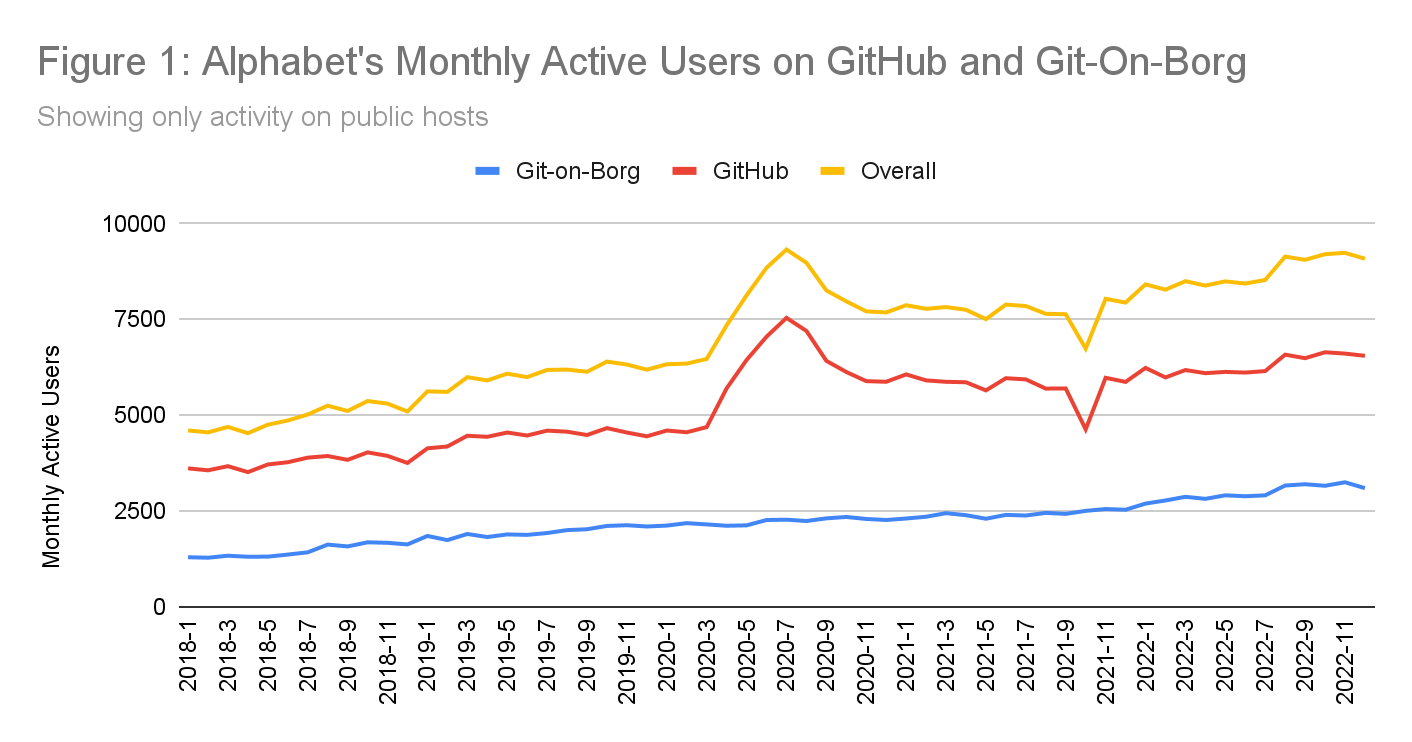

Our contributions continue to scale with our growing workforce

In 2022, roughly 10% of Alphabet's full-time workforce contributed to open source projects hosted on GitHub or Git-on-Borg - our internal production Git service (more details below). This percentage has remained roughly consistent over the last five years, indicating that our open source contribution has continued to scale with the growth of Alphabet. Similar to last year, FTEs represented over 95% of our open source workers, while the remainder includes vendors, independent contractors, temporary staff, and interns who contributed to open source projects during their tenure at Alphabet.

Our portfolio of projects remains active

We estimate that more than 2000 projects that originated from Alphabet teams and employees were still active* (not archived). To make this estimate, we chose a broad and variable definition of an open source project, including developer tools, utilities, languages, frameworks, libraries, demos, sample code, models, raw data, designs, and more.

Project counts should not be confused with repositories as projects can include many repositories. Within Alphabet, we maintain over 7500 public repositories on GitHub and 1600 public repositories on Git-on-Borg. Our total repositories under management have reduced over time with the enforcement of a new archiving policy that flags repositories for archiving based on activity levels and owner feedback. Most of these repositories are open to outside contribution: more than 500,000 unique GitHub accounts not affiliated with Alphabet workers contributed to Alphabet projects in 2022.

The majority of our open source work happens outside of Alphabet organizationsThe majority of repositories we work on are outside of Alphabet organizations: Over the last five years, more than 70% of non-personal GitHub repositories Alphabet contributors interacted with were outside of Google-managed organizations. We updated the methodology behind this metric since our last edition to filter out forks created in the pull request workflow. The top projects (by unique contributors at Alphabet) include Google-initiated projects such as Kuberenetes, Apache Beam, and gRPC as well as community-led projects such as LLVM, Envoy, and Rust.

We continue to invest in the sustainability of open source ecosystems

The mission of the Google Open Source Programs Office remains the same: we sponsor, create, and invest in projects and programs that enable everyone to join and contribute to the global open source ecosystem. In 2022, OSPO provided $5.7M in membership fees and sponsorship funding to 60 key open source projects and organizations. This funding was in addition to our established annual programs:

- In its 18th year, Google Summer of Code enabled more than 1000 individuals to contribute to more than 150 organizations. Over the lifetime of this program, more than 19,000 individuals from 112 countries have contributed to more than 800 open source organizations across the globe.

- In its fourth year, Google Season of Docs provided direct grants to 30 open source projects to hire more than 50 technical writers to improve open source project documentation, and published its second case study report highlighting useful open source documentation metrics. More than half of the documentation created in the 2022 program were how-tos, tutorials, and reference documentation; projects primarily wanted to add documentation for missing use cases and fix disorganized documentation.

- Since 2011, the Google Open Source Peer Bonus Program has awarded bonuses for open source contributions to members of our extended community. In 2022 more than 300 contributors received awards, working in over 40 countries on more than 200 open source projects.

Our open source work will continue to grow and evolve to support the changing needs of our communities. Thank you to our colleagues and community members who continue to dedicate their personal and professional time supporting the open source ecosystem. Follow our work at opensource.google.

By Sophia Vargas – Researcher, Google Open Source Programs Office

About this data:

This report features metrics provided by many teams and programs across Alphabet. In regards to the code and code-adjacent activities data, we wanted to share more details about the derivation of those metrics.

2022 updates: This year, we decided to remove event counts as it is increasingly difficult to differentiate automated activities from human-centered work. Even after filtering out non-human accounts, we couldn’t correlate these events to employee time spent on open source projects, and so we reduced our reporting to focus on our population and scope of effort.

- Data sources: These data represent activities on repositories hosted on GitHub and our internal production Git service Git-on-Borg. These sources represent a subset of open source activity currently tracked by Google OSPO.

- GitHub: We continue to use GitHub Archive as the primary source for GitHub data, which is available as a public dataset on BigQuery. Alphabet activity within GitHub is identified by self-registered accounts, which we estimate underreports actual activity.

- Git-on-Borg: This is our primary platform for internal projects and some of our larger, long running public projects such as Android and Chromium. While we continue to develop on this platform, most of our open source activity has moved to GitHub to increase exposure and encourage community growth.

- Distinct event types: Note that Git-on-Borg and GitHub APIs produce distinct sets of events—so we report activity metrics per platform. Where GitHub Event logs capture a wide range of activity from code creation and review to issue creation and comments, the Gerrit Event stream (used by Git-on-Borg) only captures code changes and reviews.

- Driven by humans: We have created many automated bots and systems that can propose changes on various hosting platforms. We have intentionally filtered these data to focus on human-initiated activities.

- Business and personal: Activity on GitHub reflects a mixture of Alphabet projects, third party projects, experimental efforts, and personal projects. Our metrics report on all of the above unless otherwise specified.

- Alphabet contributors: Please note that unless additional detail is specified, activity counts attributed to Alphabet open source contributors will include our full-time employees as well as our extended Alphabet community (temps, vendors, contractors, and interns).

- GitHub Accounts: For counts of GitHub accounts not affiliated with Alphabet, we cannot assume that one account is equivalent to one person, as multiple accounts could be tied to one individual or bot account.

- *Active counts: Where possible, we will show ‘active users’ defined by logged activity (excluding ‘WatchEvent’) within a specified timeframe (a month, year, etc.) and ‘active repositories’ and ‘active projects’ as those that have enough activity to meet our internal criteria and have not been archived.