Android is the first mobile operating system to introduce advanced cellular security mitigations for both consumers and enterprises. Android 14 introduces support for IT administrators to disable 2G support in their managed device fleet. Android 14 also introduces a feature that disables support for null-ciphered cellular connectivity.

Hardening network security on Android

The Android Security Model assumes that all networks are hostile to keep users safe from network packet injection, tampering, or eavesdropping on user traffic. Android does not rely on link-layer encryption to address this threat model. Instead, Android establishes that all network traffic should be end-to-end encrypted (E2EE).

When a user connects to cellular networks for their communications (data, voice, or SMS), due to the distinctive nature of cellular telephony, the link layer presents unique security and privacy challenges. False Base Stations (FBS) and Stingrays exploit weaknesses in cellular telephony standards to cause harm to users. Additionally, a smartphone cannot reliably know the legitimacy of the cellular base station before attempting to connect to it. Attackers exploit this in a number of ways, ranging from traffic interception and malware sideloading, to sophisticated dragnet surveillance.

Recognizing the far reaching implications of these attack vectors, especially for at-risk users, Android has prioritized hardening cellular telephony. We are tackling well-known insecurities such as the risk presented by 2G networks, the risk presented by null ciphers, other false base station (FBS) threats, and baseband hardening with our ecosystem partners.

2G and a history of inherent security risk

The mobile ecosystem is rapidly adopting 5G, the latest wireless standard for mobile, and many carriers have started to turn down 2G service. In the United States, for example, most major carriers have shut down 2G networks. However, all existing mobile devices still have support for 2G. As a result, when available, any mobile device will connect to a 2G network. This occurs automatically when 2G is the only network available, but this can also be remotely triggered in a malicious attack, silently inducing devices to downgrade to 2G-only connectivity and thus, ignoring any non-2G network. This behavior happens regardless of whether local operators have already sunset their 2G infrastructure.

2G networks, first implemented in 1991, do not provide the same level of security as subsequent mobile generations do. Most notably, 2G networks based on the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) standard lack mutual authentication, which enables trivial Person-in-the-Middle attacks. Moreover, since 2010, security researchers have demonstrated trivial over-the-air interception and decryption of 2G traffic.

The obsolete security of 2G networks, combined with the ability to silently downgrade the connectivity of a device from both 5G and 4G down to 2G, is the most common use of FBSs, IMSI catchers and Stingrays.

Stingrays are obscure yet very powerful surveillance and interception tools that have been leveraged in multiple scenarios, ranging from potentially sideloading Pegasus malware into journalist phones to a sophisticated phishing scheme that allegedly impacted hundreds of thousands of users with a single FBS. This Stingray-based fraud attack, which likely downgraded device’s connections to 2G to inject SMSishing payloads, has highlighted the risks of 2G connectivity.

To address this risk, Android 12 launched a new feature that enables users to disable 2G at the modem level. Pixel 6 was the first device to adopt this feature and it is now supported by all Android devices that conform to Radio HAL 1.6+. This feature was carefully designed to ensure that users are not impacted when making emergency calls.

Mitigating 2G security risks for enterprises

The industry acknowledged the significant security and privacy benefits and impact of this feature for at-risk users, and we recognized how critical disabling 2G could also be for our Android Enterprise customers.

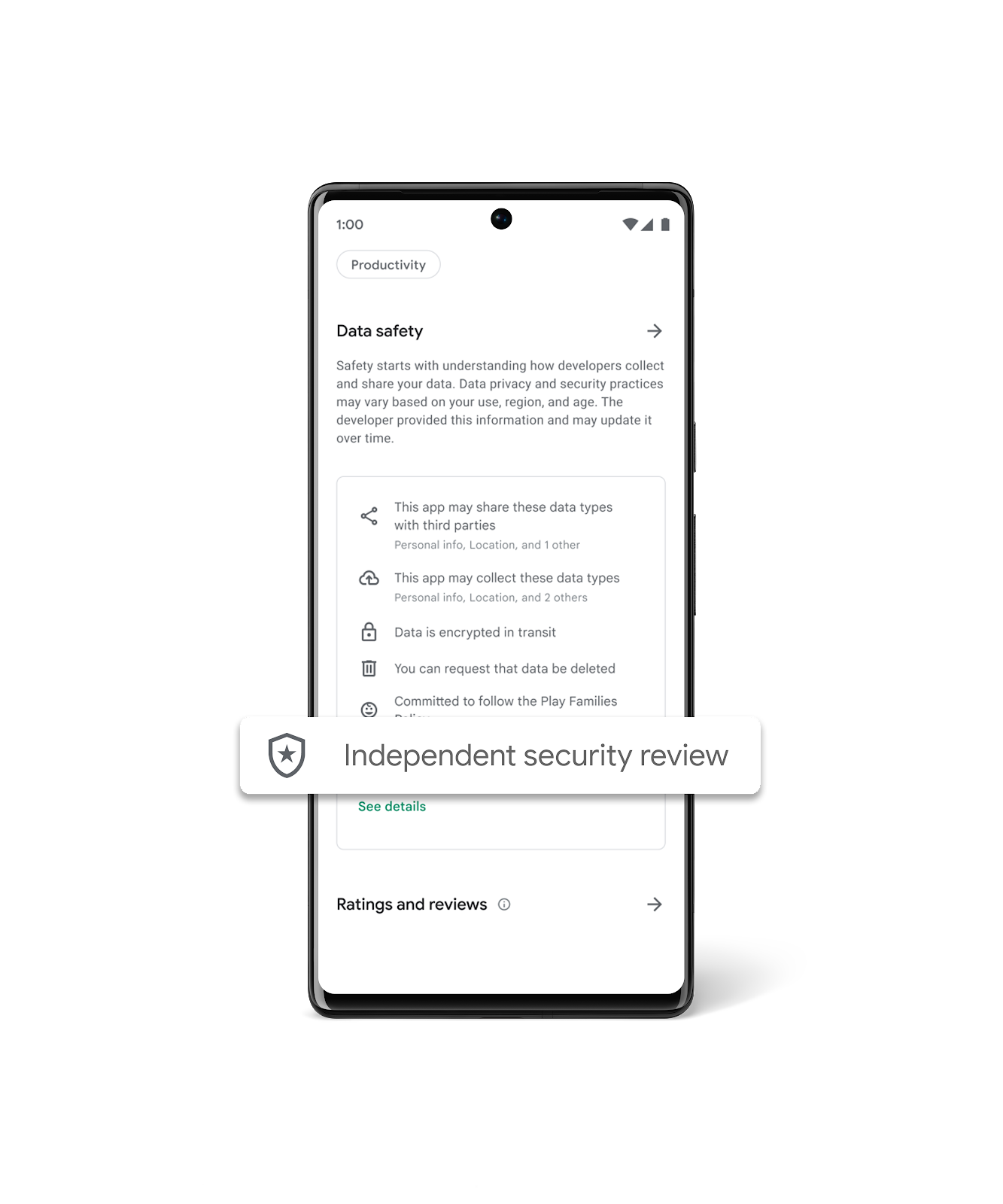

Enterprises that use smartphones and tablets require strong security to safeguard sensitive data and Intellectual Property. Android Enterprise provides robust management controls for connectivity safety capabilities, including the ability to disable WiFi, Bluetooth, and even data signaling over USB. Starting in Android 14, enterprise customers and government agencies managing devices using Android Enterprise will be able to restrict a device’s ability to downgrade to 2G connectivity.

The 2G security enterprise control in Android 14 enables our customers to configure mobile connectivity according to their risk model, allowing them to protect their managed devices from 2G traffic interception, Person-in-the-Middle attacks, and other 2G-based threats. IT administrators can configure this protection as necessary, always keeping the 2G radio off or ensuring employees are protected when traveling to specific high-risk locations.

These new capabilities are part of the comprehensive set of 200+ management controls that Android provides IT administrators through Android Enterprise. Android Enterprise also provides comprehensive audit logging with over 80 events including these new management controls. Audit logs are a critical part of any organization's security and compliance strategy. They provide a detailed record of all activity on a system, which can be used to track down unauthorized access, identify security breaches, and troubleshoot system problems.

Also in Android 14

The upcoming Android release also tackles the risk of cellular null ciphers. Although all IP-based user traffic is protected and E2EE by the Android platform, cellular networks expose circuit-switched voice and SMS traffic. These two particular traffic types are strictly protected only by the cellular link layer cipher, which is fully controlled by the network without transparency to the user. In other words, the network decides whether traffic is encrypted and the user has no visibility into whether it is being encrypted.

Recent reports identified usage of null ciphers in commercial networks, which exposes user voice and SMS traffic (such as One-Time Password) to trivial over the air interception. Moreover, some commercial Stingrays provide functionality to trick devices into believing ciphering is not supported by the network, thus downgrading the connection to a null cipher and enabling traffic interception.

Android 14 introduces a user option to disable support, at the modem-level, for null-ciphered connections. Similarly to 2G controls, it’s still possible to place emergency calls over an unciphered connection. This functionality will greatly improve communication privacy for devices that adopt the latest radio hardware abstraction layer (HAL). We expect this new connectivity security feature to be available in more devices over the next few years as it is adopted by Android OEMs.

Continuing to partner to raise the industry bar for cellular security

Alongside our Android-specific work, the team is regularly involved in the development and improvement of cellular security standards. We actively participate in standards bodies such as GSMA Fraud and Security Group as well as the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), particularly its security and privacy group (SA3). Our long-term goal is to render FBS threats obsolete.

In particular, Android security is leading a new initiative within GSMA’s Fraud and Security Group (FASG) to explore the feasibility of modern identity, trust and access control techniques that would enable radically hardening the security of telco networks.

Our efforts to harden cellular connectivity adopt Android’s defense-in-depth strategy. We regularly partner with other internal Google teams as well, including the Android Red Team and our Vulnerability Rewards Program.

Moreover, in alignment with Android’s openness in security, we actively partner with top academic groups in cellular security research. For example, in 2022 we funded via our Android Security and Privacy Research grant (ASPIRE) a project to develop a proof-of-concept to evaluate cellular connectivity hardening in smartphones. The academic team presented the outcome of that project in the last ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks.

The security journey continues

User security and privacy, which includes the safety of all user communications, is a priority on Android. With upcoming Android releases, we will continue to add more features to harden the platform against cellular security threats.

We look forward to discussing the future of telco network security with our ecosystem and industry partners and standardization bodies. We will also continue to partner with academic institutions to solve complex problems in network security. We see tremendous opportunities to curb FBS threats, and we are excited to work with the broader industry to solve them.

Special thanks to our colleagues who were instrumental in supporting our cellular network security efforts: Nataliya Stanetsky, Robert Greenwalt, Jayachandran C, Gil Cukierman, Dominik Maier, Alex Ross, Il-Sung Lee, Kevin Deus, Farzan Karimi, Xuan Xing, Wes Johnson, Thiébaud Weksteen, Pauline Anthonysamy, Liz Louis, Alex Johnston, Kholoud Mohamed, Pavel Grafov