(Crossposted on the Google Security blog)

Google My Business enables millions of business owners to create listings and share information about their business on Google Maps and Search, making sure everything is up-to-date and accurate for their customers. Unfortunately, some actors attempt to abuse this service to register fake listings in order to defraud legitimate business owners, or to charge exorbitant service fees for services.

Over a year ago, we teamed up with the University of California, San Diego to research the actors behind fake listings, in order to improve our products and keep our users safe. The full report, “Pinning Down Abuse on Google Maps”, will be presented tomorrow at the 2017 International World Wide Web Conference.

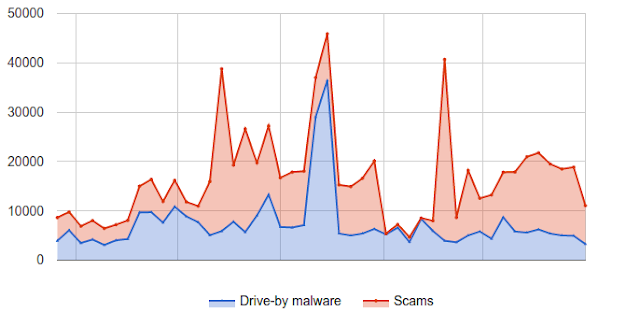

Our study shows that fewer than 0.5% of local searches lead to fake listings. We’ve also improved how we verify new businesses, which has reduced the number of fake listings by 70% from its all-time peak back in June 2015.

What is a fake listing?

For over a year, we tracked the bad actors behind fake listings. Unlike email-based scams selling knock-off products online, local listing scams require physical proximity to potential victims. This fundamentally changes both the scale and types of abuse possible.

Bad actors posing as locksmiths, plumbers, electricians, and other contractors were the most common source of abuse—roughly 2 out of 5 fake listings. The actors operating these fake listings would cycle through non-existent postal addresses and disposable VoIP phone numbers even as their listings were discovered and disabled. The purported addresses for these businesses were irrelevant as the contractors would travel directly to potential victims.

Another 1 in 10 fake listings belonged to real businesses that bad actors had improperly claimed ownership over, such as hotels and restaurants. While making a reservation or ordering a meal was indistinguishable from the real thing, behind the scenes, the bad actors would deceive the actual business into paying referral fees for organic interest.

How does Google My Business verify information?

Google My Business currently verifies the information provided by business owners before making it available to users. For freshly created listings, we physically mail a postcard to the new listings’ address to ensure the location really exists. For businesses changing owners, we make an automated call to the listing’s phone number to verify the change.

Unfortunately, our research showed that these processes can be abused to get fake listings on Google Maps. Fake contractors would request hundreds of postcard verifications to non-existent suites at a single address, such as 123 Main St #456 and 123 Main St #789, or to stores that provided PO boxes. Alternatively, a phishing attack could maliciously repurpose freshly verified business listings by tricking the legitimate owner into sharing verification information sent either by phone or postcard.

Keeping deceptive businesses out — by the numbers

Leveraging our study’s findings, we’ve made significant changes to how we verify addresses and are even piloting an advanced verification process for locksmiths and plumbers. Improvements we’ve made include prohibiting bulk registrations at most addresses, preventing businesses from relocating impossibly far from their original address without additional verification, and detecting and ignoring intentionally mangled text in address fields designed to confuse our algorithms. We have also adapted our anti-spam machine learning systems to detect data discrepancies common to fake or deceptive listings.

Combined, here’s how these defenses stack up:

- We detect and disable 85% of fake listings before they even appear on Google Maps.

- We’ve reduced the number of abusive listings by 70% from its peak back in June 2015.

- We’ve also reduced the number of impressions to abusive listings by 70%.

As we’ve shown, verifying local information comes with a number of unique anti-abuse challenges. While fake listings may slip through our defenses from time to time, we are constantly improving our systems to better serve both users and business owners.