Taking pictures of outdoor scenes at night has so far been the domain of large cameras, such as DSLRs, which are able to achieve excellent image quality, provided photographers are willing to put up with bulky equipment and sometimes tricky postprocessing. A few years ago experiments with phone camera nighttime photography produced pleasing results, but the methods employed were impractical for all but the most dedicated users.

Night Sight, introduced last year as part of the Google Camera App for the Pixel 3, allows phone photographers to take good-looking handheld shots in environments so dark that the normal camera mode would produce grainy, severely underexposed images. In a previous blog post our team described how Night Sight is able to do this, with a technical discussion presented at SIGGRAPH Asia 2019.

This year’s version of Night Sight pushes the boundaries of low-light photography with phone cameras. By allowing exposures up to 4 minutes on Pixel 4, and 1 minute on Pixel 3 and 3a, the latest version makes it possible to take sharp and clear pictures of the stars in the night sky or of nighttime landscapes without any artificial light.

The amount of light detected by the camera’s image sensor inherently has some uncertainty, called “shot noise,” which causes images to look grainy. The visibility of shot noise decreases as the amount of light increases; therefore, it is best for the camera to gather as much light as possible to produce a high-quality image.

How much light reaches the image sensor in a given amount of time is limited by the aperture of the camera lens. Extending the exposure time for a photo increases the total amount of light captured, but if the exposure is long, motion in the scene being photographed and unsteadiness of the handheld camera can cause blur. To overcome this, Night Sight splits the exposure into a sequence of multiple frames with shorter exposure times and correspondingly less motion blur. The frames are first aligned, compensating for both camera shake and in-scene motion, and then averaged, with careful treatment of cases where perfect alignment is not possible. While individual frames may be fairly grainy, the combined, averaged image looks much cleaner.

Experimenting with Exposure Time

Soon after the original Night Sight was released, we started to investigate taking photos in very dark outdoor environments with the goal of capturing the stars. We realized that, just as with our previous experiments, high quality pictures would require exposure times of several minutes. Clearly, this cannot work with a handheld camera; the phone would have to be placed on a tripod, a rock, or whatever else might be available to hold the camera steady.

Just as with handheld Night Sight photos, nighttime landscape shots must take motion in the scene into account — trees sway in the wind, clouds drift across the sky, and the moon and the stars rise in the east and set in the west. Viewers will tolerate motion-blurred clouds and tree branches in a photo that is otherwise sharp, but motion-blurred stars that look like short line segments look wrong. To mitigate this, we split the exposure into frames with exposure times short enough to make the stars look like points of light. Taking pictures of real night skies we found that the per-frame exposure time should not exceed 16 seconds.

|

| Motion-blurred stars in a single-frame two-minute exposure. |

Sixteen-second exposures allow us to capture enough light to produce recognizable images but a useable camera app capable of taking pictures that look great must deal with additional issues that are unique to low-light photography.

Dark Current and Hot Pixels

Dark current causes CMOS image sensors to record a spurious signal, as if the pixels were exposed to a small amount of light, even when no actual light is present. The effect is negligible when exposure times are short, but it becomes significant with multi-second captures. Due to unavoidable imperfections in the sensor’s silicon substrate, some pixels exhibit higher dark current than their neighbors. In a recorded frame these “warm pixels,” as well as defective “hot pixels,” are visible as tiny bright dots.

Warm and hot pixels can be identified by comparing the values of neighboring pixels within the same frame and across the sequence of frames recorded for a photo, and looking for outliers. Once an outlier has been detected, it is concealed by replacing its value with the average of its neighbors. Since the original pixel value is discarded, there is a loss of image information, but in practice this does not noticeably affect image quality.

Mobile phones use their screens as electronic viewfinders — the camera captures a continuous stream of frames that is displayed as a live video in order to aid with shot composition. The frames are simultaneously used by the camera’s autofocus, auto exposure, and auto white balance systems.

To feel responsive to the photographer, the viewfinder is updated at least 15 times per second, which limits the viewfinder frame exposure time to 66 milliseconds. This makes it challenging to display a detailed image in low-light environments. At light levels below the rough equivalent of a full moon or so, the viewfinder becomes mostly gray — maybe showing a few bright stars, but none of the landscape — and composing a shot becomes difficult.

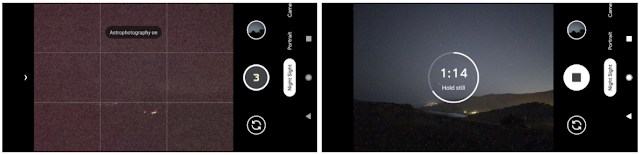

To assist in framing the scene in extremely low light, Night Sight displays a “post-shutter viewfinder”. After the shutter button has been pressed, each long-exposure frame is displayed on the screen as soon as it has been captured. With exposure times up to 16 seconds, these frames have collected almost 250 times more light than the regular viewfinder frames, allowing the photographer to easily see image details as soon as the first frame has been captured. The composition can then be adjusted by moving the phone while the exposure continues. Once the composition is correct, the initial shot can be stopped, and a second shot can be captured where all frames have the desired composition.

Autofocus ensures that the image captured by the camera is sharp. In normal operation, the incoming viewfinder frames are analyzed to determine how far the lens must be from the sensor to produce an in-focus image, but in very low light the viewfinder frames can be so dark and grainy that autofocus fails due to lack of detectable image detail. When this happens, Night Sight on Pixel 4 switches to “post-shutter autofocus.” After the user presses the shutter button, the camera captures two autofocus frames with exposure times up to one second, long enough to detect image details even in low light. These frames are used only to focus the lens and do not contribute directly to the final image.

Even though using long-exposure frames for autofocus leads to consistently sharp images at light levels low enough that the human visual system cannot clearly distinguish objects, sometimes it gets too dark even for post-shutter autofocus. In this case the camera instead focuses at infinity. In addition, Night Sight includes manual focus buttons, allowing the user to focus on nearby objects in very dark conditions.

Sky Processing

When images of very dark environments are viewed on a screen, they are displayed much brighter than the original scenes. This can change the viewer’s perception of the time of day when the photos were captured. At night we expect the sky to be dark. If a picture taken at night shows a bright sky, then we see it as a daytime scene, perhaps with slightly unusual lighting.

This effect is countered in Night Sight by selectively darkening the sky in photos of low-light scenes. To do this, we use machine learning to detect which regions of an image represent sky. An on-device convolutional neural network, trained on over 100,000 images that were manually labeled by tracing the outlines of sky regions, identifies each pixel in a photograph as “sky” or “not sky.”

|

| A landscape picture taken on a bright full-moon night, without sky processing (left half), and with sky darkening (right half). Note that the landscape is not darkened. |

Results

With the phone on a tripod, Night Sight produces sharp pictures of star-filled skies, and as long as there is at least a small amount of moonlight, landscapes will be clear and colorful.

Of course, the phone’s capabilities are not limitless, and there is always room for improvement. Although nighttime scenes are dark overall, they often contain bright light sources such as the moon, distant street lamps, or prominent stars. While we can capture a moonlit landscape, or details on the surface of the moon, the extremely large brightness range, which can exceed 500,000:1, so far prevents us from capturing both in the same image. Also, when the stars are the only source of illumination, we can take clear pictures of the sky, but the landscape is only visible as a silhouette.

For Pixel 4 we have been using the brightest part of the Milky Way, near the constellation Sagittarius, as a benchmark for the quality of images of a moonless sky. By that standard Night Sight is doing very well. Although Milky Way photos exhibit some residual noise, they are pleasing to look at, showing more stars and more detail than a person can see looking at the real night sky.

|

| Examples of photos taken with the Google Camera App on Pixel 4. An album with more pictures can be found here. |

In the course of developing and testing Night Sight astrophotography we gained some experience taking outdoor nighttime pictures with Pixel phones, and we’d like to share a list of tips and tricks that have worked for us. You can find it here.

Acknowledgements

Night Sight is an ongoing collaboration between several teams at Google. Key contributors to the project include from the Gcam team, Orly Liba, Nikhil Karnad, Charles He, Manfred Ernst, Michael Milne, Andrew Radin, Navin Sarma, Jon Barron, Yun-Ta Tsai, Tianfan Xue, Jiawen Chen, Dillon Sharlet, Ryan Geiss, Sam Hasinoff, Alex Schiffhauer, Yael Pritch Knaan and Marc Levoy; from the Super Res Zoom team, Bart Wronski, Peyman Milanfar, and Ignacio Garcia Dorado; from the Google camera app team, Emily To, Gabriel Nava, Sushil Nath, Isaac Reynolds, and Michelle Chen; from the Android platform team, Ryan Chan, Ying Chen Lou, and Bob Hung; from the Mobile Vision team, Longqi (Rocky) Cai, Huizhong Chen, Emily Manoogian, Nicole Maffeo, and Tomer Meron; from Machine Perception, Elad Eban and Yair Movshovitz-Attias.